RUSSIA IS RESURRECTING THE MISSILES OF OCTOBER IN A LARGER SCALE

The great strength of American capitalism is also its great weakness, namely, its extremely high weapons productivity. A number of factors have produced increases in productivity, like, the mechanization of the production process that got under way in England as early as the 18th century. In the early 20th century, then, American industrialists made a contribution in the form of automatiion. ..Amor Patriae

RUSSIA IS RESURRECTING THE MISSILES OF OCTOBER IN A LARGER SCALE

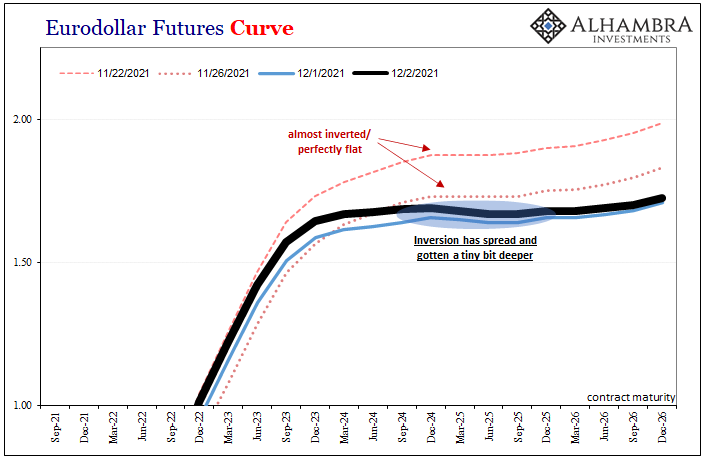

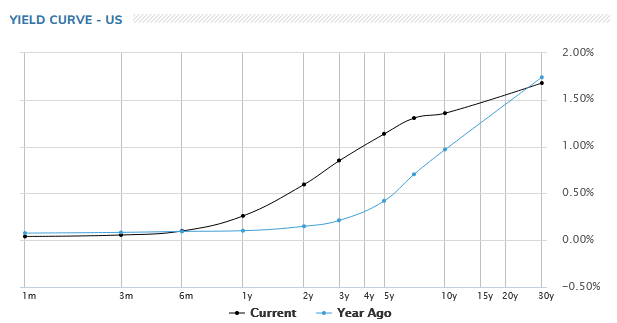

While this is a major milestone in the monetary system’s decidedly anti-inflation/growth journey, it is hardly the end point of it. On the contrary, though it takes a lot of negative, deflationary potential to distort the curve in this way, we need to see if the market sticks with that potential rather than just some flashing rush of otherwise fleeting concern (for the record, this hasn’t happened; once upside-down, it has in the past stayed upside-down).

Day 2 of inversion, and, yes, the curve is a tiny bit more overturned than yesterday. Even though the whole curve itself moved up somewhat, falling prices nearly across-the-board, therefore a higher nominal curve level, we are instead interested in the shape of it independent of how it might move up or down.

For the time being, our focus for now remains on the twisting. And we shouldn’t expect much more out of it. At least, for now.

Therefore, inversion Day One did indeed stick around for Day Two. Not good.

What might we expect over the coming weeks and months?

Using both the 2006-07 example as well as the more recent, and darn near carbon copy 2018 curve, it may be that this small amount of upside-down is all we get for some time. Though it then may seem insignificant, it is actually that amount of time rather than depth of inversion which is important as a leading indication.

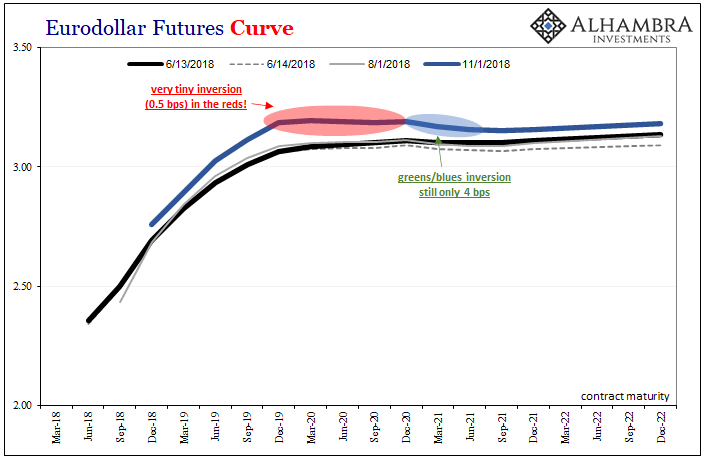

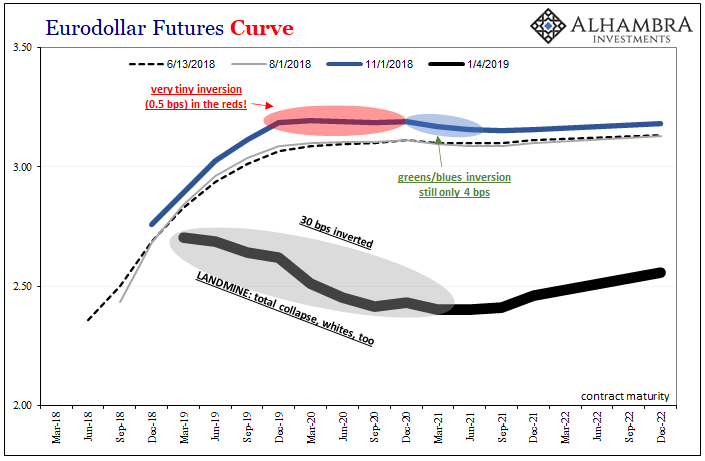

Going back to three years ago, from the initial inversion on June 13, 2018, the nominal eurodollar futures curve moved a little bit up and down throughout the summer and early autumn. It was practically unchanged until October, and then things started to heat up.

All as the eurodollar futures curve had thoroughly priced/predicted throughout the last half of 2018 right on into 2019. Even when it didn’t seem like much at all, just a few basis points, the fact those inverted few hung around and hung around, distorted the curve week after week, month after month, it was actually a very ominous warning of what was to come.

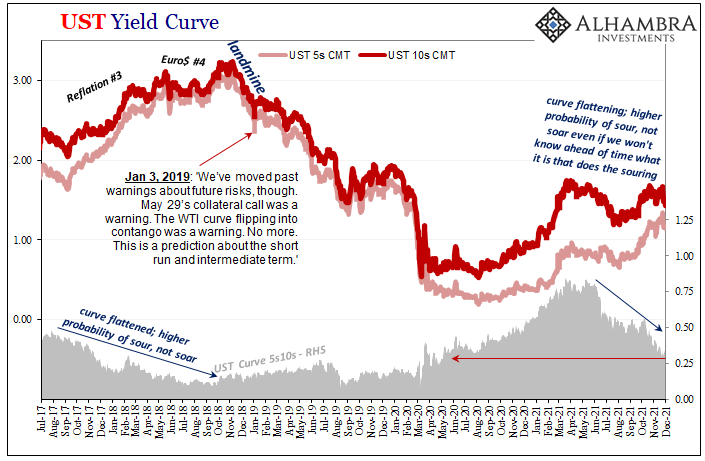

Given this example, this is what we’ll be watching – along with all the usual suspects including the flatter and flatter Treasury curve as well as what might be another crack at zero by the JGB 10s. The dollar’s rise. There are others, as well.

These things are progressions, and rather lengthy ones. In today’s day-to-day focused world, it’s easy to lose sight of what this all really means; or just get bored with it since it might not seem like anything has changed. You see an inversion and it is shocking at first, if only because it really, really shouldn’t be there. But then if or when it doesn’t really seem to do much thereafter, maybe you relax and lose focus.

Then, “suddenly”, bam, the landmine and the whole landscape changes; or, more accurately, the landscape doesn’t really change, it just becomes so obvious and obviously bad that there’s no alternative but to pay close attention.

In other words, at this stage it’s not the depth of inversion, it’s that it is and remains there at all for any further length of time. Nothing so offends the natural financial order as this; ugly and foreboding even at a outwardly minimal state.

Put it this way: if it takes quite a lot of bad vibes just to get the curve, any curve, inverted just the bare minimum (like yesterday) in the first place, what level of pessimism, skepticism, and downright risk aversion must there be hidden from within the shadows to keep it there for any length of time at any depth?

Outlook: We get the Oct trade balance tomorrow and JOLTS (Oct) on Wednesday, but have to wait for Friday for the biggie, November CPI. As noted above, the WSJ reports the ongoing rise in the 2-year note and the falling 10-year as both due to the same factors as though flattening the yield curve does not deserve any particular comment.

We never pretend to understand the bond market, but when the yield curve is flattening or even inverting, that means bond players think inflation worries are exaggerated and the Fed will not be hiking as signs of deflation/recession start appearing. Of course, a big problem is that some variables lag (including inflation) while other factors are more sprightly. One analyst points out that the main US curve and the Eurodollar yield curve are getting inverted right now.

Well, that depends on which measure you are looking at-- and there is a wide variety of data sets to choose from. FRED offers some goofy version–Commercial paper minus Fed funds, for example. See Fred’s 10-year minus the 2-year–falling, to be sure, but still positive. Besides, as a 2018 Fed article explained, inversion is not always and everywhere a harbinger of recession. This reminds us again of the Kindleberger statement that an inverted yield curve has predicted 38 of the last three recessions.

The article points out that most charts are showing nominal rates when theory demands real ones. Looking at low and falling rates as a reflection of consumers’ expected earnings (ref. Friedman’s price theory), an “inverted yield curve does not a forecast recession; instead, it forecasts the economic conditions that make recession more likely.”

Sure enough, “the real yield curve flattened and inverted prior to each of the past three recessions. Consistent with the theory, consumption growth tends to decelerate as the yield curve flattens. This is true even in non-recessionary episodes.” But the 1990 recession can be down to the Kuwait war and 2001 and then 2007-09 were asset price crashes. A flattening doesn’t necessarily portend a recession. The article was written in 2018 when the curve had been falling for several years–but we didn’t get a recession. A recession caused by a shock is far more likely when growth is already slow or slowing. But that’s not what we have now. We have very high real growth. We also have a potential shock–omicron, more delta, Russia/China–but the bond market seems to be anticipating more than it has to or is wise.

We get the JOLTS report on Wednesday. Is there anything in the labor market to stay the Fed’s hand? We don’t see it. Average hourly earnings for all employees on US private nonfarm payrolls rose by 4.8% year-on-year in November of 2021, the same pace as in the prior month but missing market estimates of 5%. The annual inflation rate in the US surged to 6.2% in October, if considerably less in refined versions (trimmed mean, etc.)

So the question becomes how much do wages have to rise to pull workers back into the workforce, or put the other way around, how much does inflation have to rise to scare them back? Our local NextDoor chatroom is full of stories of employers being too inflexible on hours and other specifics, accounting for the shortage of manned check-out lines at the supermarket and Walmart. Again, when we get the Jolts report, we need to pare the reported jobs available when they are not actually available to the existing labor force.

Now let’s consider commodity prices. You can waste an entire Sunday afternoon trying to find and load a generic benchmark commodity price index into the charting package. There are hundreds of them listed in Reuters. The Reuters versions differ from Moody’s version and they both differ from the version shown in Trading Economics, which is something based on “trading on a contract for difference (CFD) that tracks the benchmark market for this commodity,” whatever that means. But never mind–Reuters and Moody’s show pretty much the same thing–a vast rise from a low in March to May 2020 to a high in November 2021. The Reuters version starts in May and is a gain of 60% while the Moody’s version starts in March and delivers a gain of 80%. What 20% among friends? The CRB shown in TradingEconomics has the low in April and the high at end Oct for a total gain of 120%. The chart here is from Sunday afternoon.

This is frustrating but the point is that commodity prices soared starting as Covid lockdowns started to hit in the spring of 2020, whether it’s visible in March, April, or May. And they peaked in November, whether the gain is 60%, 80% or 120%. It’s a LOT. So, if we see a drop coming, and if it’s a classic 30-50% drop, what does that mean for inflation and for currencies? It’s hard to say because an index by definition contains some stuff that will get falling prices (wheat?) and some others that will not (oil).

This is why, presumably, some economists (like former TreasSec Larry Summers) are calling for an end to tariffs, which are a tax on the consumer. Keeping the Trump-era tariffs is costing the consumer $600-900/year. The Biden administration just increased the tariff on Canadian softwoods, which can only add to rising housing costs, already fairly stratospheric.

Even with some exceptions and keeping tariffs, a big drop in commodity prices will appear deflationary. The important thing to keep in mind is that the Fed doesn’t care about appearances. It cares about consumption growth and the costs of goods sold to consumers. This is what its reputation rests on. For the dollar, the implication is that if growth is going to tank in Q1 and commodity prices and inflation along with it, a delay in that first hike might be the prudent course for the Fed. But speculation along these lines, even with the evidence of the bond yields and likely commodity price crash, tends not to be useful. The Fed (and the president) need to see CPI or the PCE deflator on the decline. After all, the Fed declares itself data-dependent.

Out of this hodgepodge, the bottom line is that talk of recession is wrong or at least premature. The labor market failed to deliver the expected headline number, but other aspects of the labor market, like the participation rate and rising average earnings, are okay and even fairly good. Even if commodity prices hit a severe downturn, as seems likely, the Fed is not going to be deterred from its decision to accelerate the taper and thus to bring forward the first rate hike. Rising interest rates, or rather the expectation of rising rates, “should” be dollar supportive, especially in the context of already high rates in some emerging markets (Mexico) and in the face of rates the same and sub-zero in Europe. The problem with the comparative expected rates story is that it fails to account for the action in some currencies, notably the CAD and AUD, where central banks are expected to hike well ahead of the Fed.