| | |

The Vikings who invaded western and eastern Europe were chiefly pagans from Denmark, Norway and Sweden. They also settled in the Faroe Islands, Ireland, Iceland, Scotland (Caithness, the Hebrides and the Northern Isles), Greenland, and Canada. Their North Germanic language, Old Norse, became the mother-tongue of present-day Scandinavian languages. By 801, a strong central authority appears to have been established in Jutland, and the Danes were beginning to look beyond their own territory for land, trade and plunder. In Norway, mountainous terrain and fjords formed strong natural boundaries. Communities there remained independent of each other, unlike the situation in Denmark which is lowland. By 800, some 30 small kingdoms existed in Norway. | | | | |

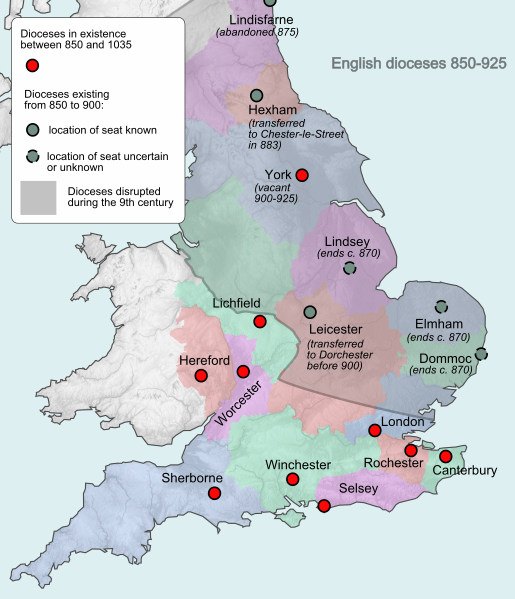

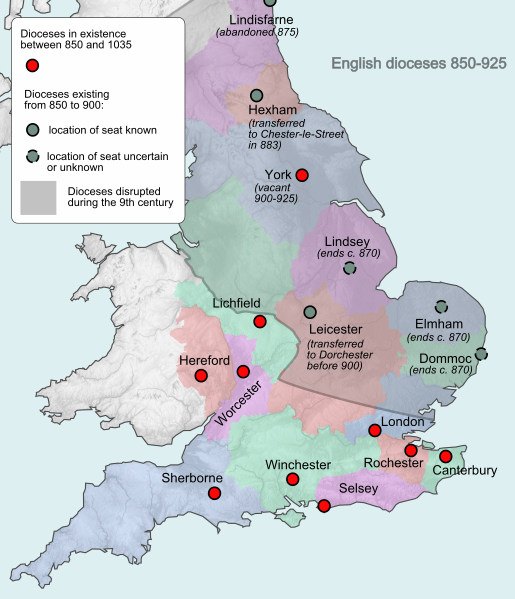

| | The sea was the easiest way of communication between the Norwegian kingdoms and the outside world. It was in the 8th century that Scandinavians began to build ships of war and send them on raiding expeditions to initiate the Viking Age. The North Sea rovers were traders, colonisers and explorers as well as plunderers. | Probable causes of Norse expansion. Norse society was based on agriculture and trade with other peoples and placed great emphasis on the concept of honour, both in combat and in the criminal justice system. It was, for example, unfair and wrong to attack an enemy already in a fight with another. It is unknown what triggered the Norse expansion and conquests. This era coincided with the Medieval Warm Period (800–1300) and stopped with the start of the Little Ice Age(about 1250–1850). The start of the Viking Age, with the sack of Lindisfarne, also coincided with Charlemagne's Saxon Wars, or Christian wars with pagans in Saxony. Historians Rudolf Simek and Bruno Dumézil theorise that the Viking attacks may have been in response to the spread of Christianity among pagan peoples. Professor Rudolf Simek believes that “it is not a coincidence if the early Viking activity occurred during the reign of Charlemagne”.[8][13] Because of the penetration of Christianity in Scandinavia, serious conflict divided Norway for almost a century. | |

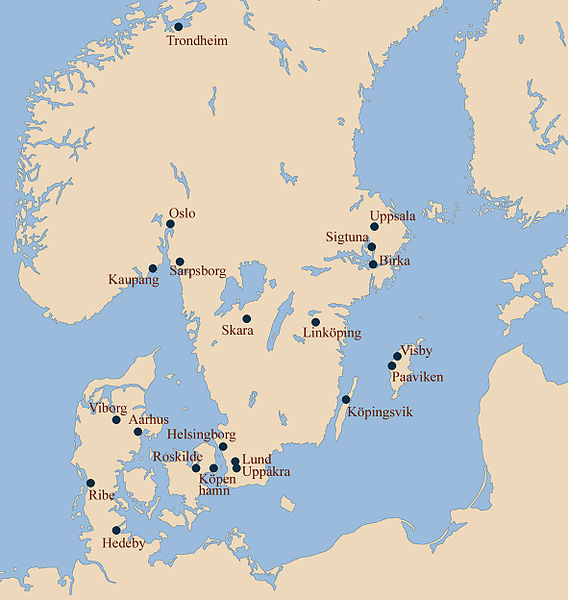

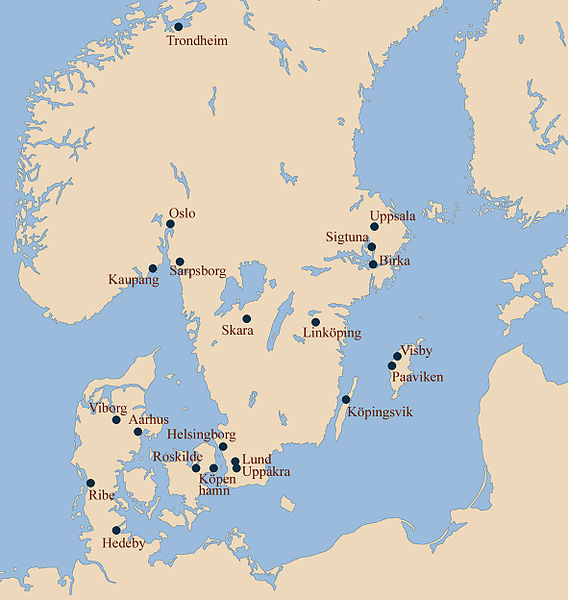

Defending A Viking group defends themselves in a battle display during the Viking Festival in Largs, Ayrshire. Viking era towns of Scandinavia. The castle is located in what was once the very volatile border area between England and Scotland. Not only did the English and Scots fight, but the area was frequently attacked by Vikings. The castle was built in 1550, around the time that Lindisfarne Priory went out of use, and stones from the priory were used as building material. It is very small by the usual standards, and was more of a fort. The castle sits on the highest point of the island, a whin stone hill called Beblowe. Lindisfarnes's position in the North Sea made it vulnerable to attack from Scots and Norsemen, and by Tudor times it was clear there was a need for a stronger fortification. This resulted in the creation of the fort on Beblowe Crag which between 1570 and 1572 formed the basis of the present castle. After Henry VIII had dissolved the priory, his troops used the remains as a naval store. Later, Elizabeth I had work carried out on the fort, strengthening it and providing gun platforms for the new developments in artillery technology. When James I came to power, he combined the Scottish and English thrones, and the need for the castle declined. At this time the castle was still garrisoned from Berwick and protected the small Lindisfarne Harbour. In the eighteenth century the castle was occupied briefly by Jacobite rebels, but was quickly recaptured by soldiers from Berwick who imprisoned the rebels; they dug their way out and hid for nine days close to nearby Bamburgh Castle before making good their escape. In later years the castle was used as a coastguard look-out and became something of a tourist attraction. Charles Rennie Mackintosh made a sketch of the old fort in 1901. In 1901, it became the property of Edward Hudson, a publishing magnate and the owner of Country Life magazine. He had it refurbished in the Arts and Crafts style by Sir Edwin Lutyens. It is said that Hudson and the architect came across the building while touring Northumberland and climbed over the wall to explore inside.' SCOTLAND BEFORE AND AFTER BRAVEHEART With the means of travel (longships and open water), their desire for goods led Scandinavian traders to explore and develop extensive trading partnerships in new territories. It has been suggested that the Scandinavians suffered from unequal trade practices imposed by Christian advocates and that this eventually led to the breakdown in trade relations and raiding. British merchants who declared openly that they were Christian and would not trade with heathens and infidels (Muslims and the Norse) would get preferred status for availability and pricing of goods through a Christian network of traders. A two-tiered system of pricing existed with both declared and undeclared merchants trading secretly with banned parties. Viking raiding expeditions were separate from and coexisted with regular trading expeditions. A people with the tradition of raiding their neighbours when their honour had been impugned might easily fall to raiding foreign peoples who impugned their honour.

St Columba's Church Bell Tower From the informational sign:

This monastery was founded by Columban monks fleeing Iona after Viking attacks. When in 807 AD the Columban monks abandoned Iona in western Scotland in the face of Vikign attacks, the abbot of Iona transferred the headquarters of the Columban monastic network to Kells, where they founded the "city". The celebrated Book of Kells, an illuminated copy of the gospels, was made about the time that the Iona community came to Ireland. In 1007 the Book of Kells was stolen from the church at Kells, but was found two months later -- covered by a sod and lacking its richly decorated cover. The original church of Kells does not survive. Outside the churchyard is St Columba's House, a small stone-roofed church. The Round Tower was mentioned in 1076 when Murchadh, who had been king of Tara, was murdered inside it; the doorway has a head carved on one of the jambs. Historians also suggest that the Scandinavian population was too large for the peninsula and there was not enough good farmland for everyone. This led to a hunt for more land. Particularly for the settlement and conquest period that followed the early raids, internal strife in Scandinavia resulted in the progressive centralization of power into fewer hands. Formerly empowered local lords who did not want to be oppressed by greedy kings emigrated overseas. Iceland became Europe's first modern republic, with an annual assembly of elected officials called the Althing, though only goði (wealthy landowners) had the right to vote there Historic overview  |

Lindisfarne Castle | | |

Defending A Viking group defends themselves in a battle display during the Viking Festival in Largs, Ayrshire. Viking era towns of Scandinavia. The castle is located in what was once the very volatile border area between England and Scotland. Not only did the English and Scots fight, but the area was frequently attacked by Vikings. The castle was built in 1550, around the time that Lindisfarne Priory went out of use, and stones from the priory were used as building material. It is very small by the usual standards, and was more of a fort. The castle sits on the highest point of the island, a whin stone hill called Beblowe. Lindisfarnes's position in the North Sea made it vulnerable to attack from Scots and Norsemen, and by Tudor times it was clear there was a need for a stronger fortification. This resulted in the creation of the fort on Beblowe Crag which between 1570 and 1572 formed the basis of the present castle. After Henry VIII had dissolved the priory, his troops used the remains as a naval store. Later, Elizabeth I had work carried out on the fort, strengthening it and providing gun platforms for the new developments in artillery technology. When James I came to power, he combined the Scottish and English thrones, and the need for the castle declined. At this time the castle was still garrisoned from Berwick and protected the small Lindisfarne Harbour. In the eighteenth century the castle was occupied briefly by Jacobite rebels, but was quickly recaptured by soldiers from Berwick who imprisoned the rebels; they dug their way out and hid for nine days close to nearby Bamburgh Castle before making good their escape. In later years the castle was used as a coastguard look-out and became something of a tourist attraction. Charles Rennie Mackintosh made a sketch of the old fort in 1901. In 1901, it became the property of Edward Hudson, a publishing magnate and the owner of Country Life magazine. He had it refurbished in the Arts and Crafts style by Sir Edwin Lutyens. It is said that Hudson and the architect came across the building while touring Northumberland and climbed over the wall to explore inside.' SCOTLAND BEFORE AND AFTER BRAVEHEART With the means of travel (longships and open water), their desire for goods led Scandinavian traders to explore and develop extensive trading partnerships in new territories. It has been suggested that the Scandinavians suffered from unequal trade practices imposed by Christian advocates and that this eventually led to the breakdown in trade relations and raiding. British merchants who declared openly that they were Christian and would not trade with heathens and infidels (Muslims and the Norse) would get preferred status for availability and pricing of goods through a Christian network of traders. A two-tiered system of pricing existed with both declared and undeclared merchants trading secretly with banned parties. Viking raiding expeditions were separate from and coexisted with regular trading expeditions. A people with the tradition of raiding their neighbours when their honour had been impugned might easily fall to raiding foreign peoples who impugned their honour.

St Columba's Church Bell Tower From the informational sign:

This monastery was founded by Columban monks fleeing Iona after Viking attacks. When in 807 AD the Columban monks abandoned Iona in western Scotland in the face of Vikign attacks, the abbot of Iona transferred the headquarters of the Columban monastic network to Kells, where they founded the "city". The celebrated Book of Kells, an illuminated copy of the gospels, was made about the time that the Iona community came to Ireland. In 1007 the Book of Kells was stolen from the church at Kells, but was found two months later -- covered by a sod and lacking its richly decorated cover. The original church of Kells does not survive. Outside the churchyard is St Columba's House, a small stone-roofed church. The Round Tower was mentioned in 1076 when Murchadh, who had been king of Tara, was murdered inside it; the doorway has a head carved on one of the jambs. Historians also suggest that the Scandinavian population was too large for the peninsula and there was not enough good farmland for everyone. This led to a hunt for more land. Particularly for the settlement and conquest period that followed the early raids, internal strife in Scandinavia resulted in the progressive centralization of power into fewer hands. Formerly empowered local lords who did not want to be oppressed by greedy kings emigrated overseas. Iceland became Europe's first modern republic, with an annual assembly of elected officials called the Althing, though only goði (wealthy landowners) had the right to vote there Historic overview | | | | | Viking era towns of Scandinavia. The castle is located in what was once the very volatile border area between England and Scotland. Not only did the English and Scots fight, but the area was frequently attacked by Vikings. The castle was built in 1550, around the time that Lindisfarne Priory went out of use, and stones from the priory were used as building material. It is very small by the usual standards, and was more of a fort. The castle sits on the highest point of the island, a whin stone hill called Beblowe. Lindisfarnes's position in the North Sea made it vulnerable to attack from Scots and Norsemen, and by Tudor times it was clear there was a need for a stronger fortification. This resulted in the creation of the fort on Beblowe Crag which between 1570 and 1572 formed the basis of the present castle. After Henry VIII had dissolved the priory, his troops used the remains as a naval store. Later, Elizabeth I had work carried out on the fort, strengthening it and providing gun platforms for the new developments in artillery technology. When James I came to power, he combined the Scottish and English thrones, and the need for the castle declined. At this time the castle was still garrisoned from Berwick and protected the small Lindisfarne Harbour. In the eighteenth century the castle was occupied briefly by Jacobite rebels, but was quickly recaptured by soldiers from Berwick who imprisoned the rebels; they dug their way out and hid for nine days close to nearby Bamburgh Castle before making good their escape. In later years the castle was used as a coastguard look-out and became something of a tourist attraction. Charles Rennie Mackintosh made a sketch of the old fort in 1901. In 1901, it became the property of Edward Hudson, a publishing magnate and the owner of Country Life magazine. He had it refurbished in the Arts and Crafts style by Sir Edwin Lutyens. It is said that Hudson and the architect came across the building while touring Northumberland and climbed over the wall to explore inside.' SCOTLAND BEFORE AND AFTER BRAVEHEART | | | | |

| Pottery from Africa found in a burnt-out fortress in Galloway hints at a 'lost' Dark Ages kingdom that may even have been born of an alliance between Britons and Picts. Remarkably, a Pictish carved stone at the fort's entrance shows two entwined symbols which could have been evidence of an alliance between Britons and Picts, possibly through a ‘royal’ marriage. A shard of sixth century pottery from Africa also found at the site shows it could only have been home to someone of ‘the very highest status’, like a King. | | The Picts were a savage tribe who lived north of the Firth of Forth - very few Pictish stones have ever been found outside their traditional territory.

A newly found spearhead dates from around that time, while sixth century pottery from Africa shows it could only have been home to someone of ¿the very highest status¿ like a King | | Anglo-Saxon hoard revealed: 4,000 pieces of stunning handcrafted treasure hint that Beowolf's description of 'golden warriors' is true -

A total of 4,000 pieces of the Staffordshire Hoard have been brought together for experts to study at Birmingham Museum and Gallery and include fragments of helmet and gold sword decorations engraved with animals

-

Experts have discovered more than 600 new links, joins and associations between the parts -

Discovery has shed new light on the Anglo-Saxon poem Beowulf as the description of a warrior’s adornment in gold is now thought to be more realistic than experts previously believed

-

Saxon hoard was discovered in 2009 and is considered one of the most important ever found

An incredible hoard of precious Anglo-Saxon gold items, the likes of which professional archaeologists dream of finding, was discovered buried in a field by a jobless treasure hunter five years ago. And now all 4,000 pieces of the Staffordshire Hoard have been brought back together for the first time, allowing experts to shed some light on life in the Dark Ages. They believe the precious artefacts, which range from fragments of helmet to gold sword decorations engraved with animals and encrusted with jewels, are a ‘true archaeological mirror’ to the great Anglo-Saxon poem Beowulf.

+14 Reunited: All 4,000 pieces of the Staffordshire Hoard have been brought back together for the first time, allowing experts (pictured) to shed some light on life in the dark ages. They believe the artefacts, which range from fragments of helmet to gold sword decorations, are a ¿true archaeological mirror¿ to the great Anglo-Saxon poem Beowulf The intricate pieces of gold, silver and garnet, many of which show highly detailed craftsmanship, were laid out and assembled on a table in a back room at Birmingham Museum and Gallery. By putting all the pieces of Anglo-Saxon gold in one place, experts have discovered more than 600 new links and associations between the parts. Now shattered pieces of sword decoration and helmet are being put back together like pieces of a jigsaw puzzle, to give experts an improved understanding of the once buried treasure and its significance.

+14 Experts believe the precious artefacts, which range from fragments of helmet to gold sword decorations engraved with animals and encrusted with jewels (pictured), are a 'true archaeological mirror' to the Anglo-Saxon poem Beowulf

+14

+14 The intricate pieces of gold, silver and garnet, many of which show highly detailed craftsmanship, were laid out and assembled on a table in a back room at Birmingham Museum and Gallery. These two artefacts are examples of early Christian crosses The skills of the ancient jewellers are striking, with threads of gold less than a millimetre thick wound into elegant patterns, and tiny pieces of red and blue garnet stone that have been carved into elaborate curved shapes to fit into sword decorations. Other pieces include snakes, horses and even marching warriors. One item initially thought to be a seahorse has been now identified to be a pair of stylised horses linked together with a wolf. The experts also discovered that the vast majority of the hoard would have been owned or used by soldiers, showing that it was not just kings who went into battle with their weaponry and armour decorated with gold and intricate jewellery. HOARD RESEARCH - WHAT THE EXAMINATION OF THE ARTEFACTS REVEALED -

The number of artefacts in the collection now stands at 4,000, after more than the first 500 objects found were revealed in nearby fields - including a garnet bird mount. -

Many broken fragments have been joined together into their original objects such as new types of sword fittings and other mounts. -

Groups of sword fittings have been matched to show what original sword hilts looked like. -

At least one helmet, composed of over 1,500 pieces, is contained in the treasure. Anglo-Saxon helmets are incredibly rare in Britain - only five were previously known. -

The sword and weaponry fittings show for the first time the true extent of the gold wealth and aspirations of the ruling warrior class of early England. Previously, only glimpses of these warriors had been revealed in exceptional burials like Sutton Hoo. -

The analysis has revealed much new information about how the objects were constructed including: the composition of the alloys used, the joining of metal with woods and animal horn plus the glues and resins made of animal and plant extracts. -

A variety of types of Saxon and re-used Roman glass has also been identified.

+14 By putting all the pieces of Anglo-Saxon gold in one place, (pictured) experts have discovered more than 600 new links, joins and associations between the parts. Now shattered pieces of sword decoration and helmet are being put back together like pieces of a jigsaw puzzle, to give experts an ever changing view of the buried treasure

+14

+14 The skills of the ancient jewellers are easily apparent with threads of gold less than a millimetre thick wound into intricate shapes, and tiny pieces of red and blue garnet stone that have been carved into elaborate, curved shapes to fit into sword pommel decorations. Other pieces show snakes, horses (pictured left) and warriors (right) THE DISCOVERY OF THE HOARD A treasure hunter made a find that professional archaeologists dream of in 2009. It was the most valuable hoard of Saxon gold in history - estimated to be worth £3.3million - and includes 500 pieces such as gold sword hilts, jewels from Sri Lanka and early Christian crosses. The 1,300-year-old treasure was discovered by unemployed Terry Herbert in July in a field owned by a friend in Staffordshire. Within days, the 55-year-old former coffin factory worker from Walsall had filled 244 bags with gold objects weighing in at more than 11lbs (5kg). Mr Herbert, who bought an old metal detector for £2.50 18 years ago, said he was overwhelmed by the find – regarded as one of the most important in decades. ‘I have this phrase that I say sometimes – “spirits of yesteryear take me where the coins appear” – but on that day I changed coins to gold,’ he said. ‘I don’t know why I said it that day, but I think somebody was listening and directed me to it. Maybe it was meant to be, maybe the gold had my name on it all along. ‘I was going to bed and in my sleep I was seeing gold items.’ The jewels are thought to have come from Sri Lanka - carried to Europe by traders. The gold probably came from the Byzantine Empire, the eastern remnant of the Roman Empire based in what is now Istanbul. The treasure dates from 675 and 725AD, the time of Beowulf – the great Anglo-Saxon poem. Historian Chris Fern said that the unique discovery has shed new light on the Anglo-Saxon poem Beowulf. The description of a warrior’s adornment in gold was thought to have been exaggerated, but experts are starting to see that it could have been closer to the truth following the study of the Hoard. ‘The great poem Beowulf, once believed to be artistic exaggeration, now has a true mirror in archaeology. We thought it was a piece of exaggeration, or poetic spin,’ he said. ‘We did not think that this much gold was carried by the warrior class but the Staffordshire Hoard has revolutionised our understanding of this period.’ David Symons, curator of antiquities and numismatics at Birmingham Museum explained that the exercise of laying out all the piece of the hoard together has been ‘crucial’ to examining each piece’s function. ‘For the first time we’ve been able to lay out all the pieces of the hoard, look at them, try to piece things together, group things together by the decoration on them and as a result we’ve made huge advances, including 600 joins and associations,’ he said. Mr Symons explained that they have been able to find pieces that were clearly linked together and in other cases see where designs matched and items may have been made by the same jeweller or goldsmith. ‘It’s like a giant jigsaw puzzle, we have lots of small pieces which eventually we can build into something,’ he said. One of the more unusual aspects of the Hoard is that much of the study has taken place publically. Traditionally when there is an archaeological find, experts take the items and study them, draw conclusions and publish their findings and only then do the items find their way into museums or public display. The Staffordshire Hoard, apart from some early cataloguing, went on display within weeks of its discovery and items have been cleaned and studied while others are on display in Birmingham, Stoke, Tamworth and Lichfield. ‘We knew at the start there was this massive public interest in the find,’ said Mr Symons. ‘By doing it this way we also gathered a huge and unprecedented response to the public fund raising appeal which allowed us to buy the hoard. This has been a strength of this find, that there has been all this interest. It’s been wonderful.’ The hoard was discovered near the village of Hammerwich in a farmer’s field next to the A5 in July 2009 by treasure hunter Terry Herbert using his metal detector. A second batch was found nearby in November 2012. At the time it was hidden, Staffordshire was the heartland of Mercia, an aggressive kingdom under the rule of King Aethelred and other rulers.

+14 The experts also discovered that the vast majority of the Hoard would have been owned or used by soldiers, showing that it was not just kings who went into battle with their weaponry and armour decorated with gold and intricate jewellery

+14 The hoard was discovered near the village of Hammerwich (pictured) in a farmer's field next to the A5 in July 2009 by treasure hunter Terry Herbert using his metal detector. A second batch was found nearby in November 2012 The gold could have been collected during wars with the kingdoms of Northumbria and East Anglia. Some appears to have been deliberately removed from the objects to which they were attached. Some of the items have been bent and twisted. It may have been hurriedly buried when the owner was in danger. The fact it was never recovered suggests the owner was killed, experts said. It may also have been buried by a victorious army as a form of humiliation to the defeated. Fred Johnson, the farmer on whose land the treasure was discovered, joined conservationists to see all of the collection laid out in a cleaned state for the first time.

+14 Historian Chris Fern (pictured here examining fragments of the hoard) said that the unique discovery has shed new light on the Anglo-Saxon poem Beowulf. The description of a warrior's adornment in gold was thought to have been exaggerated, but experts are starting to see that it could have been closer to the truth following the study of the hoard ‘This is the first time that I have seen the treasure like this in four years and it is even more amazing than before. I am very privileged to own the field where this treasure was found. ‘The field itself is very fertile and I have grown everything in it – it is amazing to think that potatoes and carrots had been growing in the same place as ancient buried treasure. ‘The snakes are my favourite artefacts and I was spellbound when I saw them for the first time.’ The hoard was valued at £3.3million and bought by Birmingham and Stoke-on-Trent museums following a fundraising appeal.

+14 The hoard, which includes this intricately carved gold plate was discovered near the village of Hammerwich in a farmer's field next to the A5 in July 2009 by treasure hunter Terry Herbert using his metal detector. A second batch was found nearby in November 2012

+14 It was the most valuable hoard of Saxon gold in history and includes 500 pieces such as gold sword hilts, jewels from Sri Lanka (pictured) and early Christian crosses

+14 The hoard (pictured) has once again been broken up this week and pieces shipped out to the museums that form the 'Mercian Trail' where pieces are now on show The hoard has once again been broken up this week and pieces shipped out to the museums that form the ‘Mercian Trail’ where pieces are now on show. Work is underway on a new exhibition at Birmingham Museum and Art Gallery to display the Hoard in a purpose-built gallery and provide visitors with an insight into the Anglo-Saxon world. It is due to open in September. Visitors to Stoke-on-Trent’s Potteries Museum will be able to see 180 pieces from the hoard displayed in a recreated seventh century mead hall as part of an exhibition showing the life and times of the Anglo-Saxon Midlands.

+14 At the time it was hidden, Staffordshire was the heartland of Mercia, an aggressive kingdom. The gold could have been collected during wars with the kingdoms of Northumbria and East Anglia. Some appears to have been deliberately removed from the objects to which they were attached. Some of the items have been bent and twisted (pictured) HAVE VALUABLE ARTEFACTS BEEN STOLEN FROM A NEWLY DISCOVERED ANGLO-SAXON SETTLEMENT? Night-hawkers may have stripped some of the most valuable artefacts from a newly discovered Anglo-Saxon royal settlement, archaeologists have warned.

Coins found at the Rendlesham site: Last night the National Trust confirmed in a statement that the finds represented 'conclusive evidence of the existence of the long-lost Royal settlement at Rendlesham' The discovery of the high-status settlement on fields near the village of Rendlesham, Suffolk, was made public this week after more than five years of work. But as about 70 finds which point to a site of international significance go on show to the public, those behind the search said they had been forced to act by illegal metal-detector users scouring the site illegally. A plan has been put in place with Suffolk Police to protect what remains after the discovery was announced. Sir Michael Bunbury, who owns the farmland, said he had contacted local council archaeologists after becoming concerned about illegal night-time activity. He said: 'The sad thing is, it is impossible to know exactly what has been lost. We will never know what it was, where it is and it can't contribute to our wider understanding of this site. 'It is fair to speculate that some very valuable artefacts indeed have been removed and sold privately because of course that is exactly what night-hawkers are after. 'The good news is that, despite this criminal activity, there has still been a very significant find. By legitimately searching the site and putting the finds on public display, we have effectively put the problem on our land to a stop. 'Perhaps this is a lesson in how to put that kind of activity to a halt.' 'The problem had escalated over three years with trails of foot prints and trenches appearing on Sir Michael's land, often soon after ploughing. They seemed to know what was going on on our land,' he added. 'It seemed like quite an organised operation supported by a degree of local knowledge. We are nervous about what might happen now the discovery is receiving publicity but we have a plan in place with the police so they will act at the first sign of a problem.' Judith Plouviez, the project manager and Suffolk County Council archaeologist, condemned the activity, saying: 'There were clearly people selling valuable objects which they had no right to do.' She added: 'It's always a problem when people dig things out of the ground illegally - they're tearing up pages of history and we will never be able to recover that. 'It is particularly unfortunate here because those objects would have added to our knowledge of a very important site.'

Hidden treasure: Archaeologists believe they have found an ancient royal settlement which once spread across more than 100 acres of what is now farmland at Naunton Hall in Rendlesham (pictured) near Woodbridge, Suffolk Despite the potential losses, archaeologist say the discoveries provide conclusive evidence of a long-lasting and major settlement. It is thought fragments of gold jewellery, Saxon pennies and weights associated with trade, are evidence of the 'the king's country-seat of Rendlesham' mentioned by the Venerable Bede in the 8th century. Professor Christopher Scull, of Cardiff University and University College London said: 'The survey has identified a site of national and indeed international importance for the understanding of the Anglo-Saxon elite and their European connections. 'The quality of some of the metalwork leaves no doubt that it was made for and used by the highest ranks of society. These exceptional discoveries are truly significant in throwing new light on early East Anglia and the origins of Anglo-Saxon kingdoms.' Sutton Hoo is the site of two 6th and early 7th century cemeteries, one of which contained an undisturbed ship burial including a wealth of artefacts and is considered one of the great discoveries of the 20th century. It is widely believed that King Raedwald, ruler of the East Angles, was buried there. It has long been thought that King Raedwald's hall stood in Rendlesham. A team of legitimate metal-detector users have been working on the farmland for the last five years after Sir Michael called for assistance. Aerial photography, chemical analysis and geophysics were also used in the search, overseen by Suffolk County Council in conjunction with the National Trust. The newly discovered 50-hectare site is four miles north-east of Sutton Hoo

No remains of any royal palace or buildings have been found but the fragments of jewellery and coins have convinced archaeologists that it was the site of a royal village. The items will go on display to the public at the Sutton Hoo visitor centre in an exhibition beginning on Saturday before being moved to Ipswich museum. Battle of Clontarf One of the last major battles involving Vikings was the Battle of Clontarf on the 23 April 1014, in which Vikings fought both for the Irish over-king Brian Boru's army and for the Viking-led army opposing him. Irish and Viking literature depict the Battle of Clontarf as a gathering of this world and the supernatural. For example, witches, goblins, and demons were present. A Viking poem portrays the environment as strongly pagan. Valkyries chanted and decided who would live and die.[20] Scotland Scandinavian Scotland While there are few records, the Vikings are thought to have led their first raids in Scotland on the holy island of Iona in 794, the year following the raid on the other holy island of Lindisfarne, Northumbria. In 839, a large Norse fleet invaded via the River Tay and River Earn, both of which were highly navigable, and reached into the heart of the Pictish kingdom of Fortriu. They defeated Eogán mac Óengusa, king of the Picts, his brother Bran and the king of the Scots of Dál Riata, Áed mac Boanta, along with many members of the Pictish aristocracy in battle. The sophisticated kingdom that had been built fell apart, as did the Pictish leadership, which had been stable for more than a hundred years since the time of Óengus mac Fergusa (The accession of Cináed mac Ailpín as king of both Picts and Scots can be attributed to the aftermath of this event). Earldom of Orkney By the mid-9th century the Norsemen had settled in Shetland, Orkney (the Nordreys- Norðreyjar), the Hebrides and Man, (the Sudreys- Súðreyjar - this survives in the Diocese of Sodor and Man) and parts of mainland Scotland. The Norse settlers were to some extent integrating with the local Gaelic population (see-Gall Gaidheal) in the Hebrides and Man. These areas were ruled over by local Jarls, originally captains of ships or Hersirs. The Jarl of Orkney and Shetland however, claimed supremacy. In 875, King Harald Fairhair led a fleet from Norway to Scotland. In his attempt to unite Norway, he found that many of those opposed to his rise to power had taken refuge in the Isles. From here, they were raiding not only foreign lands but were also attacking Norway itself. He organised a fleet and was able to subdue the rebels, and in doing so brought the independent Jarls under his control, many of the rebels having fled to Iceland. He found himself ruling not only Norway, but the Isles, Man and parts of Scotland. In 876 the Gall-Gaidheal of Man and the Hebrides rebelled against Harald. A fleet was sent against them led by Ketil Flatnose to regain control. On his success, Ketil was to rule the Sudreys as a vassal of King Harald. His grandson Thorstein the Red and Sigurd the Mighty, Jarl of Orkney invaded Scotland were able to exact tribute from nearly half the kingdom until their deaths in battle. Ketil declared himself King of the Isles. Ketil was eventually outlawed and fearing the bounty on his head fled to Iceland. The Gall-Gaidheal Kings of the Isles continued to act semi independently, in 973 forming a defensive pact with the Kings of Scotland and Strathclyde. In 1095, the King of Mann and the Isles Godred Crovan was killed by Magnus Barelegs, King of Norway. Magnus and King Edgar of Scotland agreed a treaty. The islands would be controlled by Norway, but mainland territories would go to Scotland. The King of Norway nominally continued to be king of the Isles and Man. However, in 1156, The kingdom was split into two. The Western Isles and Man continued as to be called the "Kingdom of Man and the Isles", but the Inner Hebrides came under the influence of Somerled, a Gaelic speaker, who was styled 'King of the Hebrides'. His kingdom was to develop latterly into the Lordship of the Isles. In eastern Aberdeenshire the Danes invaded at least as far north as the area near Cruden Bay.[21] The Jarls of Orkney continued to rule much of Northern Scotland until 1196, when Harald Maddadsson agreed to pay tribute to William the Lion, King of Scots for his territories on the Mainland. The end of the Viking age proper in Scotland is generally considered to be in 1266. In 1263, King Haakon IV of Norway, in retaliation for a Scots expedition to Skye, arrived on the west coast with a fleet from Norway and Orkney. His fleet linked up with those of King Magnus of Man and King Dougal of the Hebrides. After peace talks failed, his forces met with the Scots at Largs, in Ayrshire. The battle proved indecisive, but it did ensure that the Norse were not able to mount a further attack that year. Haakon died overwintering in Orkney, and by 1266, his son Magnus the Law-mender ceded the Kingdom of Man and the Isles, with all territories on mainland Scotland to Alexander III, through the Treaty of Perth. Orkney and Shetland continued to be ruled as autonomous Jarldoms under Norway until 1468, when King Christian I pledged them as security on the dowry of his daughter, who was betrothed to James III of Scotland. Although attempts were made during the 17th and 18th centuries to redeem Shetland, without success,[22] and Charles II ratifying the pawning in the 1669 Act for annexation of Orkney and Shetland to the Crown, explicitly exempting them from any "dissolution of His Majesty’s lands",[23] they are currently considered as being officially part of the United Kingdom.[24][25] Wales was not colonised by the Vikings as heavily as eastern England. The Vikings did, however, settle in the south around St. David's, Haverfordwest, and Gower, among other places. Place names such as Skokholm, Skomer, and Swansea remain as evidence of the Norse settlement.[26] The Vikings, however, did not subdue the Welsh mountain kingdoms. [edit]Iceland According to Sagas, Iceland was discovered by a viking from Sweden, after which it was settled by mostly Norwegians fleeing the oppressive rule of Harald Fairhair (late 9th century). While harsh, the land allowed for a pastoral farming life familiar to the Norse. According to the saga of Erik the Red, when Erik was exiled from Iceland he sailed west and pioneered Greenland. [edit]Greenland The Viking Age settlements in Greenland were established in the sheltered fjords of the southern and western coast. They settled in three separate areas along approximately 650 kilometres of the western coast. While harsh, the microclimates along some fjords allowed for a pastoral lifestyle similar to that of Iceland. [edit]Southern and eastern Europe

Map showing the major Varangian trade routes: the Volga trade route (in red) and theTrade Route from the Varangians to the Greeks(in purple). Other trade routes of the 8th-11th centuries shown in orange. The Varangians or Varyags (Russian, Ukrainian: Варяги, Varyagi) sometimes referred to as Variagians were Scandinavians, often Swedes, who migrated eastwards and southwards through what is now Russia and Ukraine mainly in the 9th and 10th centuries. Engaging in trade, piracy and mercenary activities, they roamed the river systems and portages of Gardariki, reaching the Caspian Sea and Constantinople. Contemporary English publications also use the name "Viking" for early Varangians in some contexts.[27][28] The term Varangian remained in usage in the Byzantine Empire until the 13th century, largely disconnected from its Scandinavian roots by then. Having settled Aldeigja (Ladoga) in the 750s, Scandinavian colonists were probably an element in the early ethnogenesis of the Rus' people, and likely played a role in the formation of the Rus' Khaganate. The Varangians (Varyags, in Old East Slavic) are first mentioned by the Primary Chronicle as having exacted tribute from the Slavic and Finnictribes in 859. It was the time of rapid expansion of the Vikings in Northern Europe; England began to pay Danegeld in 859, and the Curonians of Grobin faced an invasion by the Swedes at about the same date.

Guests from Overseas, Nicholas Roerich (1899) In 862, the Finnic and Slavic tribes rebelled against the Varangian Rus, driving them overseas back to Scandinavia, but soon started to conflict with each other. The disorder prompted the tribes to invite back the Varangian Rus "to come and rule them" and bring peace to the region. This was a somewhat bilateral relation with the Varagians defending the cities that they ruled. Led by Rurikand his brothers Truvor and Sineus, the invited Varangians (called Rus') settled around the town of Novgorod(Holmgard). In the 9th century, the Rus' operated the Volga trade route, which connected Northern Russia (Gardariki) with the Middle East (Serkland). As the Volga route declined by the end of the century, the Trade route from the Varangians to the Greeks rapidly overtook it in popularity. Apart from Ladoga and Novgorod, Gnezdovo and Gotland were major centres for Varangian trade.[29] Western historians tend to agree with the Primary Chronicle that these Scandinavians founded Kievan Rus' in the 880s and gave their name to the land.[30] Many Slavic scholars are opposed to this theory of Germanic influence on the Rus' (people) and have suggested alternative scenarios for this part of Eastern European history. In contrast to the intense Scandinavian influence in Normandy and the British Isles, Varangian culture did not survive to a great extent in the East. Instead, the Varangian ruling classes of the two powerful city-states of Novgorod and Kiev were thoroughly Slavicised by the end of the 10th century. Old Norse was spoken in one district of Novgorod, however, until the 13th century. Central Europe Further information: Pomerania during the Early Middle Ages Viking Age Scandinavian settlements were set up along the southern coast of the Baltic Sea, primarily for trade purposes. Their appearance coincides with the settlement and consolidation of the Slavic tribes in the respective areas.[31] Scandinavians had contacts to the Slavs since their very immigration, these first contacts were soon followed by both the construction of Scandinavian emporia and Slavic burghs in their vicinity.[32] The Scandinavian settlements were larger than the early Slavic ones, their craftsmen had a considerably higher productivity, and in contrast to the early Slavs, the Scandinavians were capable of seafaring.[32] Their importance for trade with the Slavic world however was limited to the coastal regions and their hinterlands.[33]

Stone ships at Altes Lager Menzlin Scandinavian settlements at the Mecklenburgian coast include Reric (Groß Strömkendorf) on the eastern coast of Wismar Bay,[34] and Dierkow (nearRostock).[35] Reric was set up around the year 700,[34] but following later warfare between Obodrites and Danes, the merchants were resettled toHaithabu.[35] Dierkow prospered from the late 8th to the early 9th century.[32] Scandinavian settlements at the Pomeranian coast include Wollin (on the isle of Wollin), Ralswiek (on the isle of Rügen), Altes Lager Menzlin (at the lower Peene river),[36] and Bardy-Świelubie near modern Kolobrzeg (Kolberg).[37] Menzlin was set up in the mid-8th century.[34] Wollin and Ralswiek began to prosper in the course of the 9th century.[35] A merchants' settlement has also been suggested near Arkona, but no archeological evidence supports this theory.[38] Menzlin and Bardy-Świelubie were vacated in the late 9th century,[39] Ralswiek made it into the new millennium, but at the time when written chronicles reported the site in the 12th century it had lost all its importance.[35] Wollin, thought to be identical with legendary Vinetaand semilegendary Jomsborg, base of the Jomsvikings, was destroyed by the Danes in the 12th century. Scandinavian arrowheads from the 8th and 9th centuries were found between the coast and the lake chains in the Mecklenburgian and Pomeranianhinterlands, pointing at periods of warfare between the Scandinavians and Slavs.[35] Scandinavian settlements existed along the southeastern Baltic coast in Truso and Kaup (Old Prussia), and in Grobin (Courland, Latvia). Trade emporia of the Viking Age (Baltic Sea) Western Europe France The French region of Normandy takes its name from the Viking invaders who were called Normannorum, which means ‘men of the North.’ The first Viking raids began between 790 and 800 along the coasts of western France. They were carried out primarily in the summer, as the Vikings wintered in Scandinavia. Several coastal areas were lost during the reign of Louis the Pious (814–840). But the Vikings took advantage of the quarrels in the royal family caused after the death of Louis the Pious to settle their first colony in the south-west (Gascony) of the kingdom of Francia, which was more or less abandoned by the Frankish kings after their two defeats at Roncevaux. The incursions in 841 caused severe damage to Rouen and Jumièges. The Vikings attackers sought to capture the treasures stored at monasteries, easy prey given the monks' lack of defensive capacity. In 845 an expedition up the Seine reached Paris. The presence of Carolingian deniers of ca 847, found in 1871 among a hoard at Mullaghboden, County Limerick, where coins were neither minted nor normally used in trade, probably represent booty from the raids of 843-6.[40] After 851, Vikings began to stay in the lower Seine valley for the winter. Twice more in the 860s Vikings rowed to Paris, leaving only when they acquired sufficient loot or bribes from theCarolingian rulers. The Carolingian kings tended to have contradictory politics, which had severe consequences. In 867, Charles the Bald signed the Treaty of Compiègne, by which he agreed to yield the Cotentin Peninsula to the Breton king Salomon, on the condition that Salomon would take an oath of fidelity and fight as an ally against the Vikings. Nevertheless, in 911 the Viking leader Rollon forced Charles the Simple to sign the Treaty of Saint-Clair-sur-Epte, under which Charles gave Rouen and the area of present-day Upper Normandy to Rollon, establishing the Duchy of Normandy. In exchange, Rollon pledged vassalage to Charles in 940, agreed to be baptised, and vowed to guard the estuariesof the Seine from further Viking attacks. While many buildings were pillaged, burned, or destroyed by the Viking raids, ecclesiastical sources may have been overly negative as no city was completely destroyed. On the other hand, many monasteries were pillaged and all the abbeys were destroyed. Rollon and his successors brought about rapid recoveries from the raids. The Scandinavian colonization was principally Danish, with a strong Norwegian element. A few Swedes were present. The merging of the Scandinavian and native elements contributed to the creation of one of the most powerful feudal states of Western Europe. The naval ability of the Normans would allow them to conquer England and southern Italy, and play a key role in the Crusades. After 842, when the Vikings set up a permanent base at the mouth of the Loire River, they could strike as far as northern Spain.[41] They attacked Cadiz in AD 844. In some of their raids they were crushed either by Kingdom of Asturias or Emirate armies. These Vikings were Hispanised in all Christian kingdoms, while they kept their ethnic identity and culture in Al-Andalus.[42] In 1015, a Viking fleet entered the river Minho and sacked the episcopal city of Tui (Galicia); no new bishop was appointed until 1070.[43] [edit]Portugal In 844, many dozens of drakkars appeared in the "Mar da Palha" ("the Sea of Straw", mouth of the Tagus river). After a siege, the Vikings conquered Lisbon (at the time, the city was under Muslim rule and known as Al-Ushbuna). They left after 13 days, following a resistance led by Alah Ibn Hazm and the city's inhabitants. Another raid was attempted in 966, without success. Other territories North America Main article: L'Anse aux Meadows In about 986, Bjarni Herjólfsson, Leif Ericson and Þórfinnr Karlsefni from Greenland reached North America and attempted to settle the land they called Vinland. They created a small settlement on the northern peninsula of present-day Newfoundland, near L'Anse aux Meadows. Conflict with indigenous peoples and lack of support from Greenland brought the Vinland colony to an end within a few years. The archaeological remains are now a UN World Heritage Site.[44] [edit]Old Norse influence on the English language The long-term linguistic effect of the Viking settlements in England was threefold: over a thousand Old Norse words eventually became part of Standard English; numerous places in the East and North-east of England have Danish names, and many English personal names are of Scandinavian origin.[45] Scandinavian words that entered the English language included landing, score, beck, fellow, take, busting and steersman.[45] The vast majority of loan words did not appear in documents until the early 12th century; these included many modern words which used sk- sounds, such as skirt, sky, and skin; other words appearing in written sources at this time included again, awkward, birth, cake, dregs, fog, freckles, gasp, law, moss, neck, ransack, root, scowl, sister, seat, sly, smile, want, weak and window from Old Norse meaning "wind-eye".[45]Some of the words that came into use are among the most common in English, such as to go, to come, to sit, to listen, to eat, both, same, get and give. The system of personal pronouns was affected, with they, them and their replacing the earlier forms. Old Norse influenced the verb to be; the replacement of sindon by are is almost certainly Scandinavian in origin, as is the third-person-singular ending -s in the present tense of verbs. There are more than 1,500 Scandinavian place names in England, mainly in Yorkshire and Lincolnshire (within the former boundaries of the Danelaw): over 600 end in -by, the Scandinavian word for "farm" — for example Grimsby, Naseby and Whitby;[46] many others end in -thorpe ("village"), -thwaite ("clearing"), and -toft ("homestead").[45] The distribution of family names showing Scandinavian influence is still, as an analysis of names ending in -son reveals, concentrated in the north and east, corresponding to areas of former Viking settlement. Early medieval records indicate that over 60% of personal names in Yorkshire and North Lincolnshire showed Scandinavian influence.[45] [edit]Technology

Modern replica of a Viking longship Further information: Viking ship, Viking Age arms and armour The Vikings were equipped with the technologically superior longships; for purposes of conducting trade however, another type of ship, the knarr, wider and deeper in draft, were customarily used. The Vikings were competent sailors, adept in land warfare as well as at sea, and they often struck at accessible and poorly defended targets, usually with near impunity. The effectiveness of these tactics earned Vikings a formidable reputation as raiders and pirates. Chroniclers paid little attention to other aspects of medieval Scandinavian culture. This slant was accentuated by the absence of contemporary primary source documentation from within the Viking Age communities themselves. Little documentary evidence was available until later, when Christian sources began to contribute. As historians and archaeologists have developed more resources to challenge the one-sided descriptions of the chroniclers, a more balanced picture of the Norsemen has become apparent. The Vikings used their longships to travel vast distances and attain certain tactical advantages in battle. They could perform highly efficient hit-and-run attacks, in which they quickly approached a target, then left as rapidly before a counter-offensive could be launched. Because of the ships' negligible draft, the Vikings could sail in shallow waters, allowing them to invade far inland along rivers. The ships' speed was also prodigious for the time, estimated at a maximum of 14–15 knots (26–28 km/h). The use of the longships ended when technology changed, and ships began to be constructed using saws instead of axes. This led to a lesser quality of ships. While battles at sea were rare, they would occasionally occur when Viking ships attempted to board European merchant vessels in Scandinavian waters. When larger scale battles ensued, Viking crews would rope together all nearby ships and slowly proceed towards the enemy targets. While advancing, the warriors hurled spears, arrows, and other projectiles at the opponents. When the ships were sufficiently close, melee combat would ensue using axes, swords, and spears until the enemy ship could be easily boarded. The roping technique allowed Viking crews to remain strong in numbers and act as a unit, but this uniformity also created problems. A Viking ship in the line could not retreat or pursue hostiles without breaking the formation and cutting the ropes, which weakened the overall Viking fleet and was a burdensome task to perform in the heat of battle. In general, these tactics enabled Vikings to quickly destroy the meagre opposition posted during raids.[47] Together with an increasing centralization of government in the Scandinavian countries, the old system of leidang — a fleet mobilization system, where every skipen (ship community) had to deliver one ship and crew — was discontinued. Changes in shipbuilding in the rest of Europe led to the demise of the longship for military purposes. By the 11th and 12th centuries, European fighting ships were built with raised platforms fore and aft, from which archers could shoot down into the relatively low longships. The nautical achievements of the Vikings were exceptional. For instance, they made distance tables for sea voyages that were remarkably precise. They have been found to differ only 2-4% from modern satellite measurements, even on such long distances as across the Atlantic Ocean. The archaeological find known as the Visby lenses from the Swedish island of Gotland may be components of a telescope. It appears to date from long before the invention of the telescope in the 17th century.[48] Recent evidence suggests that the Vikings also made use of an optical compass as a navigation aid, using the light-splitting and polarization-filtering properties of Iceland spar to find the location of the sun when it was not directly visible.[49] An archaeological find in Sweden consists of a bone fragment fixated with in-operated material; the piece is as yet undated. These bones might be the remains of a trader from the Middle East. [edit]Religion See also: Norse paganism and Norse mythology [edit]Trade centres

Fortified Viking Period town Aros (Aarhus) 950 AD

Fortified Viking Period town Aros Some of the most important trading ports during the period include both existing and ancient cities such as Aarhus(Denmark), Ribe (Denmark), Hedeby (Germany), Vineta (Pomerania), Truso (Poland), Kaupang (Norway), Birka(Sweden), Bordeaux (France), York (England), Dublin (Ireland) and Aldeigjuborg (Russia). [edit]Settlements outside Scandinavia -

British Isles and Ireland England Ireland Isle of Man Scotland -

Western Europe -

Eastern Europe In Lerwick, the capital of Scotland's Shetland Islands, a fire festival named Up Helly Aa is held every January to mark the end of the yule season. Local participants called guizers celebrate their Norse heritage, dressing in Viking gear and marching through town with battle axes and torches as they drag a ceremonial Viking longboat. At the end of the procession, the guizers hurl their torches onto the longboat and set it ablaze. After the flames die down, guizers sing the traditional song "The Norseman's Home" before a night of partying.

Flames engulf a viking longboat as it is set on fire during the Up Helly Aa fire festival in Lerwick, Shetland Islands, Scotland, on January 29, 2013.(Reuters/David Moir)

2 Participants dressed as Vikings prepare to participate in the annual Up Helly Aa festival in Lerwick, on January 29, 2013.(Andy Buchanan/AFP/Getty Images) #

3 A young participant dressed as a Viking prepares for Up Helly Aa in Lerwick, on January 29, 2013. (Andy Buchanan/AFP/Getty Images) #

4 A man dressed as a Viking has his hair braided for Up Helly Aa in Lerwick, on January 29, 2013. (Andy Buchanan/AFP/Getty Images) #

5 Participants, guizers, dressed as Vikings prepare for Up Helly Aa in Lerwick, on January 29, 2013. (Andy Buchanan/AFP/Getty Images) #

6 Guizers march during the annual Up Helly Aa festival in Lerwick, on January 29, 2013. (Andy Buchanan/AFP/Getty Images) #

7 Young Jarl Squad vikings shout as they march through the streets on the morning of the Up Helly Aa fire festival in Lerwick, on January 29, 2013. (Reuters/David Moir) By the middle of the 9th century the Norsemen had moved into the Pictish Kingdom. In the west they attacked the Scots of the Kingdom of Dalriada, who had expanded north into Argyll and Uist. The Scots/Picts capital near Dunstaffnage near Oban, was threatened and under the leadership of Kenneth MacAlpin, the Scots moved inland, towards Scone on the East coast. The Vikings helped the Scots and southern Picts create an enlarged Kingdom called Alba, with Scone (pronounced Skun or Skoon), as its capital. On the Stone of Scone, Kenneth MacAlpin, already king of Scots, was made King of Picts. The famous Stone had very religious and ceremonial ancestory to the Scots dating back to the 6th - 7th century, and earlier, when the stone is said to have been brought by Fergus to Dalriada to crown the Kings of Scots. (This stone was stolen from the Scots by Edward I "longshanks" of England in the 1296). At this point in time, circa mid 9th century, the Scots themselves only represented 1/10 (10%) of Scotland's people. They became dominate through battle and marriage. The Celtic (pronounced Keltic) Scots passed Kingship down through the male line. The Celtic Picts, by way of the female. Therefore, Scots marriages, over time, to Picts put and end to the Pictish system and they became part of Scottish society. The Picts were, due to their own rules of lineage, in essence, married out of existence as a named race. Obviously, they were still around, just called Scots now. All this was due to the male lineage taking precedence of Kingship of the Celtic Scots. But this does not mean the Picts disappeared, just assimilated into Scots and Viking society.

8 Members of the 2013 "Jarl Squad" during the Up Helly Aa procession on the Shetland Islands, on January 29, 2013.(Andy Buchanan/AFP/Getty Images) In these genetically mixing years, men broke the meager soil, planted grain, hunted on their beloved horses, (especially the Picts who where by all accounts expert horsemen), herded cattle, carved their Pictish stones with loving care, and built a mix of Christian Churches and pagan fires, and led perfectly normal lives. As already mentioned, there was a new and more deadly enemy to the Scot-Picts, and an enemy of all in their way. The slender Longships of the Norse raiders, determined and hearty men, (reportedly many were over six feet tall, which for those days was like being seven feet tall today), and also as earlier mentioned -- they invaded at will, all of the British Isles, Europe, Russia and elsewhere for plunder and slaves. Interestingly the Vikings, who were already overpopulated, didn't in fact take many slaves, but they did take the women they wanted.

Kenneth MacAlpin, King of Scots

9 Jarl Squad vikings shout during Up Helly Aa in Lerwick, on January 29, 2013. (Reuters/David Moir) In 839, an interesting battle took place. Some Picts were fighting the rebellious Scots under Alpin of Gabhran's house, a large army of Norsemen came upon their rear. Though Alpin was killed, and his head impaled by the Picts -- the Pictish army now turned to face the Norsemen and were destroyed in a wild pitched battle. The Picts not only lost to the Norsemen, they were "destroyed almost to their very number". Eoghann, the last King of Picts, died with them and now there was no Pictish leader to oppose the Scots. Why the Norsemen took part in a battle between Picts and Scots, that did not involve the Norsemen, is really easily explained. The Norsemen believed to die in battle was a sure way of entering Vahala, the great warriors reward in "Asgaard", and because of this pagan belief, the Vikings showed or had no fear of dying in combat. They happened upon the battle between the Picts and Scots, which the Scots were losing, and promptly attacked the winners -- the Picts. Besides the last of the Pictish Kings dying in the battle, so did Scots King Alpin. Kenneth the Hardy, son of Scots slain King Alpin, avenged his fathers death by taking the remaining territory of the Picts. His ascendency to King of Scots and Picts, was not a peaceful one though. The first king of Scots and Picts, (southern Picts), MacAlpin, it is said, murdered seven Earls of Dalriada, kinsmen who might have disputed his claim to King of Scots and Picts, all this took place during a celebration banquet at Scone. The ascendency of Kings was a bloody and treacherous affair -- not for the faint of heart, (or stomach in this case). One would think that after a history making battle such as the one above described would be a dramatic turning point and famous in all history books. Curiously this didn't happen, and the reason is, most likely, that it actually took another century, and more battles, before the union was a stable union of Pict and Scot. In time, however, it did become stable and the Scots gained tremendous lands, wealth, and access to expert horsemanship, as well as countless more Scottish subjects, from the fall of the Picts. The two peoples had been locked in ferocious combat for so long that the bonds of war had actually helped unite the people, as two metals in a great flame, they became fused and then were tempered by a cooling hand of Christianity.

10 Members of the Jarl Squad light torches during Up Helly Aa, on January 29, 2013. (Andy Buchanan/AFP/Getty Images) Kenneth MacAlpin was the first King of Picts and Scots, the same title given to the brother and then the son who succeeded him. The Picts pass from history as most unknown races do, and also with them, the Kingdom of Dalriada, though the evocative memory of that would last for a thousand years among the western Clans. The Vikings were another story. As already stated, it is worth mentioning again the importance the Norse and Danish had, not only on Scotland alone, but to all of the British Isles and France, Spain, Germany, Russia, countries in Eastern Europe, and the Mediterrainian, as in Sicily, and North Africa. It seems amazing to this author how little credit we as a modern society give to the Vikings as settlers as well as invaders. If you are descended from Europe, there is a very good chance the Vikings had some effect on your heritage. In Scotland they invaded then settled. The Norsemen had easy pickings in early Scotland, which at the time was a confused collection of rival kinglets, prior to MacAlpin. It was not until 843 that the country was united under already mentioned Kenneth MacAlpin, a Scot who now ruled Scots and Picts. When Kenneth MacAlpin died in the latter half of the 9th century, Scotland went through a series of mediocre kings who were kept very busy trying to hold the Norsemen out of Scotland and keep its borders fixed. Three kings died in battle, others had short reigns. The Scots unity held, but barely. One hundred and sixty years of Norse invasions and counter attacks occurred, led by, only partially successful kings, (three of whom died in battle) and then, finally the Vikings began to settle more than invade. The unity did not keep the Norsemen out. They took Dumbarton, on the River Clyde, and lorded it over the area, and they were the death of Scots' Kings, Constantine, Donald the Second and Indulf. They were the kings in a time when not many Scottish kings died in their beds. Turbulence was never far from the surface, and a king was liable to be struggling against the Norsemen, and new territorial aggression from England, as well as the uncurable rebelliousness of the men of Moray in the north. It was not until Malcolm II arrived on the throne in 1005, that the country even acquired, at last, a geographical unity with fixed borders. Malcolm II vainly tried to extend his borders to occupy parts of the north of England, but had his armies cut to pieces.

11 Guizer Jarl Stephen Grant stands on a doomed Viking longboat before it is set on fire during the Up Helly Aa fire festival in Lerwick, on January 29, 2013. (Reuters/David Moir) England also had trouble with the Vikings, the Danes (a generic term the English called all Vikings), had been invading England and now began to thirst for England's land. They took nearly half of England by force and then demanded to be paid to stop further aggression. Actually, it was an English king's idea to pay the money, or "Danegeld" (Dane gold) as it came to be known, to halt the Viking attacks. This "ransom" or Danegeld was at first successful, and the Danes left the rest of England alone......for a while. However, the idea of easy pickings, the Danegeld, was just too much for the Vikings to resist and they began to demand more and more payment of Danegeld from the English, at this point in time, England was in serious crisis. Plus they (the Danes) were now settling large areas of England and marrying the locals. The villages in the north and east of England still have many Viking names. Eventually the Danes became so powerful in England, one of their own became King of England. This was King Cnut who took the English throne in 1016. King Cnut of England (pronounced Kanewt) now began to eye Scotland, especially the Lothian area which he considered belonged to him by right. What right isn't clear. His forces went to repossess it in 1018, and the combined Britons and Scots massacred them on the banks of the River Tweed, at a battle called Carham in 1018, under the King of Scotland Malcolm II, a descendent of Kenneth MacAlpin. The army they defeated was an Angle army from Northumbria, which brought the rich Lothians under Malcolm II's rule. Scotland, and her borders, were now stable, but not necessarily for long. Meanwhile, in the farthest southwest corner of England, Alfred the Great and his descendents, made a stand against the Danes and won a series of victories, which led in time, to the Saxons reclaiming England. The Vikings, remained however, slowly mixing with Britain and in all of Europe with the native populations and eventually the "Age of the Vikings" comes to a gradual end.

Alba grew even more:

----------------------------

12 Members of the Jarl Squad circle the longboat with torches during Up Helly Aa, on January 29, 2013. (Andy Buchanan/AFP/Getty Images) In the same year as the Scottish victory at Carham, 1018, the King of the Britons of Strathclyde died without issue (no heir) and was succeeded by Malcom II's grandson and heir -- Duncan, (who was not the ageing and venerable monarch portrayed by Shakespeare in "MacBeth"), Duncan had some type of claim to the throne of Strathclyde through the female line. Exactly how he did this isn't clear, but 16 years later, in 1034, Duncan became King of Scotland. In this way the frontiers of the Scottish Kingdom were still further extended, reaching far down into what is now English territory.

The Last of the Great Scottish Kings

---------------------------------------- Duncan I of Scotland, was actually, (as opposed to the more well known Shakespeare version), an impetuous and spoiled young man whose six years of kingship brought glory neither to Scotland nor to his family. Against wise advice, Duncan invaded Northumbria and attacked Durham. The poorly planned campaign was a total disaster for the Scots and Duncan was compelled to withdraw. News of his disasterous and humiliating defeat had preceeded his return to Scotland and in no time he was faced with a revolt among the lords, particularly from his cousin MacBeth, Mormaer (or lord) of Moray. In a skirmish at Bothgouanan, Duncan was slain by MacBeth. Duncan had come to the throne by a strange set of claims to succession. MacBeth had a much better claim, as far as strict descent was concerned: so had his wife, Grauch, who was his cousin. (Not unusual in those days). Both MacBeth and his wife were descended from Kenneth MacAlpin, and the Moray party were keen to have MacBeth the new ruler of Scotland. Again, reality is much different from legend, and as you will see, MacBeth was not at all the same MacBeth portrayed in fiction. Of course I refer, again to Shakespeare's, excellent, but inaccurate version "MacBeth" with whom most of us are familiar. It is a beautiful work of art and fiction, but it is far from reality and worse, gives a good impression of Duncan, while giving a bad version of MacBeth. Royality murdering each other was, almost like a game, in all medieval history, and was quite common and even encouraged among all countries.

13 Members of the Jarl Squad light more torches during the annual Up Helly Aa festival in Lerwick, on January 29, 2013.(Andy Buchanan/AFP/Getty Images) Under MacBeth, north and south Scotland were united and a stable Scottish kingdom looked likely. MacBeth appears, contrary to popular belief, to have been a wise monarch who ruled Scotland successfully for seventeen properous years. Coming to power, (in a time, where differing peoples, who were trying to adjust to unity at the same time, but didn't want to give up their own ways of life, which were not always compatibale with those of their neighbours), he organized troops of men to patrol the wilder countryside and enforce some kind of law and order. An example of how stable the kingdom was under MacBeth, was that he was able to make a pilgrimage to Rome in 1050, returned to find his kingdom quiet and went on to enjoy seven more years of successful rule. There is actually so much to MacBeth's life prior and during his reign that is generally unknown and is very fascinating. I plan, some time in the future, to devote a whole work to MacBeth -- the greatest of early medieval Scottish kings. He did have his battles, and he dealt with them as decisively as he did every other aspect of his rule, but that is another story.......... Unfortunately, MacBeth (who had just united Scotland for 17 years) was killed in the year 1057. One of Duncan's sons, Malcolm, (known as Ceanmor or Canmore, meaning 'big head'), who was brought up in exile in England, raised an army (with English help), invaded Scotland and reached deep into Aberdeenshire. At the battle of Lumphanan, he defeated MacBeth, who was slain in battle, and after some further resistance, he became king of Scotland, calling himself Malcolm III -- with English help. NEVER again were the emerging Kings of England to leave Scotland alone. There are times in history that one could say were turning points, without being overly dramatic, MacBeth's reign, had it continued ..... well, Scotland might now rule England. The north of Britain would absorb the life giving red of the Scots and English for seven more centuries of brutal carnage.

14 The Jarl Squad starts throwing torches at the longboat during Up Helly Aa in Lerwick, on January 29, 2013.(Andy Buchanan/AFP/Getty Images) #

15 During Up Helly Aa, a Viking longboat starts to go up in flames, in Lerwick, on January 29, 2013. (Andy Buchanan/AFP/Getty Images) #

16 A members of the Jarl Squad watches the longboat burn, on January 29, 2013. (Andy Buchanan/AFP/Getty Images) #

17 Flames engulf the longboat during Up Helly Aa, on January 29, 2013. (Reuters/David Moir) #

18 Embers from the burning longboat blow past members of the 2013 Jarl Squad in Lerwick, on January 29, 2013.(Andy Buchanan/AFP/Getty Images) #

19 The Jarl Squad, during Up Helly Aa, on January 29, 2013. (Andy Buchanan/AFP/Getty Images) #

20 The Viking longboat is consumed by fire in Lerwick, Shetland Islands, on January 29, 2013. (Andy Buchanan/AFP/Getty Images) #

21 Flames engulf the dragon's head of the viking longboat as it burns during the Up Helly Aa fire festival in Lerwick, Shetland Islands, Scotland, on January 29, 2013. (Reuters/David Moir) | | | | | | | | William Wallace

'This is the truth I tell you:

of all things freedom’s most fine.

Never submit to live, my son,

in the bonds of slavery entwined.’

William Wallace - His Uncle’s proverb,

from Bower’s Scotichronicon c.1440’s The reputation of William Wallace runs like a fault line through later medieval chronicles. For the Scots, William Wallace was an exemplar of unbending commitment to Scotland’s independence who died a martyr to the cause. For centuries after its publication, Blind Harry’s 15th-century epic poem, ‘The Wallace’, was the second most popular book in Scotland after the Bible.

For the English chroniclers he was an outlaw, a murderer, the perpetrator of atrocities and a traitor. How did an obscure Scot obtain such notoriety?

Who was William Wallace?

Wallace was the younger son of a Scottish knight and minor landowner. His name, Wallace or le Waleis, means the Welshman, and he was probably descended from Richard Wallace who had followed the Stewart family to Scotland in the 12th century. Little is known of Wallace’s life before 1297. He was certainly educated, possibly by his uncle - a priest at Dunipace - who taught him French and Latin. It’s also possible, given his later military exploits, that he had some previous military experience. Wallace’s Rising

In 1296 Scotland had been conquered. Beneath the surface there were deep resentments. Many of the Scots nobles were imprisoned, they were punitively taxed and expected to serve King Edward I in his military campaigns against France. The flames of revolt spread across Scotland. In May 1297 Wallace slew William Heselrig, the English Sheriff of Lanark. Soon his rising gained momentum, as men ‘oppressed by the burden of servitude under the intolerable rule of English domination’ joined him ‘like a swarm of bees’. From his base in the Ettrick Forest his followers struck at Scone, Ancrum and Dundee. At the same time in the north, the young Andrew Murray led an even more successful rising. From Avoch in the Black Isle, he took Inverness and stormed Urquhart Castle by Loch Ness. His MacDougall allies cleared the west, whilst he struck through the north east. Wallace’s rising drew strength from the south, and, with most of Scotland liberated, Wallace and Murray now faced open battle with an English army.  On 11th September Wallace and Murray achieved a stunning victory at the Battle of Stirling Bridge. The English left with 5,000 dead on the field, including their despised treasurer, Hugh Cressingham, whose flayed skin was taken as a trophy of victory and to make a belt for Wallace’s sword. The Scots suffered one significant casualty, Andrew Murray, who was badly wounded and died two months later. On 11th September Wallace and Murray achieved a stunning victory at the Battle of Stirling Bridge. The English left with 5,000 dead on the field, including their despised treasurer, Hugh Cressingham, whose flayed skin was taken as a trophy of victory and to make a belt for Wallace’s sword. The Scots suffered one significant casualty, Andrew Murray, who was badly wounded and died two months later.

'Commander of the Army of the Kingdom of Scotland’ - the outlaw Wallace was now knighted and made Guardian of Scotland in Balliol’s name at the forest kirk, at either Selkirk or Carluke.

It was a remarkable achievement for a mere knight to hold power over the nobles of Scotland. In a medieval world obsessed with hierarchy, Wallace’s extraordinary military success catapulted him to the top of the social ladder. He now guided Scottish policy. Letters were dispatched to Europe proclaiming Scotland’s renewed independence and he managed to obtain from the Papacy the appointment of the patriotic Bishop Lamberton to the vacant Bishopric of St Andrews.

Militarily he took the war into the north of England, raiding around Newcastle and wreaking havoc across the north. Contemporary English chroniclers accused him of atrocities, some no doubt warranted, however, in Wallace’s eyes the war, since its beginning, had been marked by brutality and butchery.

|

| The Pictish stone is one of very few found outside the tribe's traditional territory north of the Firth of Forth - and hints at a possible alliance between Picts and Britons in the Dark Ages

A spearhead from the burnt-out fort on Trusty's Hill, which archaeologists now think may have been the centre of a lost Dark Ages kingdom WHO WERE THE PICTS? THE TRIBE WHO HELD OUT IN THE NORTH

Mel Gibson's blue face paint in Braveheart is a nod to the Pictish tradition of body-paint - but the real Picts fought stark naked, and there are records of them doing so up until the 5th Century. The Roman name for the people - Picti - means 'painted people'. It's not known what they called themselves. The habit of fighting naked, especially in the cold Scottish climate, didn't harm the tribe's reputation for ferocity. Picts held the territory north of the Firth of Forth in Scotland - and were one of the reasons even heavily armoured Roman legions could not conquer the area. It's long been debated how the Picts and their Southern neighbours the Britons interacted with one another. The discoveries in Galloway hint that the two might have allied, at least briefly - before the fort was burnt to the ground. ‘At Trusty's Hill we see a Z-rod and double disc which is a classic Pictish symbol. The other symbol on the stone is a fish monster with a sword, which is unique to this site. ‘It could be that we are seeing an alliance between the Picts and local Britons - two crests coming together, almost like a coat of arms.’

Mr Toolis said the vital find was the African pottery, however. He said: ‘This pottery shard, which looks like part of the rim of a bowl, is African Red Slip Ware, which came from Carthage and dates to the sixth century AD.

‘It is very rare in British, let alone Scottish Dark Age sites - the early Christian monasteries at Whithorn and Iona being the only other Scottish sites we can think of.

‘It not only indicates that Trusty's Hill was inhabited at the same time as when one would expect the Pictish Carvings to have been made but it means that very high status people in post-Roman Scotland lived here.

‘We might be discovering the evidence to show that Trusty's Hill was a stronghold of the Dark Age Kings of Galloway. ‘It could even be further evidence that the Dark Age Kingdom of Rheged, thought to have been located somewhere between Wales and Ayrshire, may actually have been in Dumfries and Galloway.’

Trusty's Hill was excavated in 1960, when vitrified stone - subjected to intense heat and effectively melted - was first identified.

The fort had clearly been burnt down, possibly at the hands of a Northumbrian enemy.